SOLSTICE

Peter Frank, Art Critic

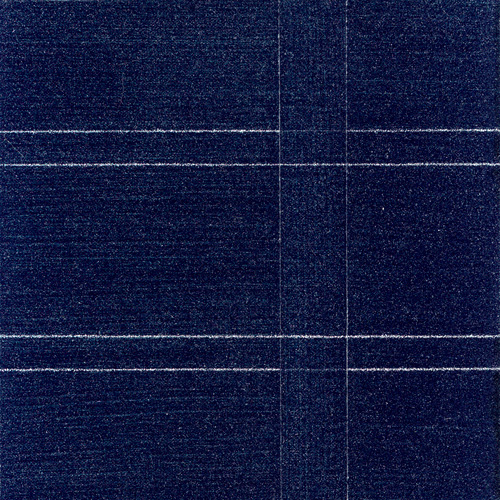

Dean Andrews’ Solstice series displays an admixture of gesture and structure, expansiveness and restraint. Each keyed to a single color, they shimmer with other colors hidden amidst the brushstrokes, colors that range from complementary to slightly dissonant but that in the aggregate give each painting depth, complexity, and atmosphere.

Dean Andrews’ Solstice series displays an admixture of gesture and structure, expansiveness and restraint. Each keyed to a single color, they shimmer with other colors hidden amidst the brushstrokes, colors that range from complementary to slightly dissonant but that in the aggregate give each painting depth, complexity, and atmosphere.

Andrews’ chromatic scale deliberately avoids the extremes of luminosity and matte dullness; rather, the coloristic presence here is rich, balanced, and alluring without being either showy or self-effacing.

These paintings breathe but they breathe in a regular, even rhythmic manner, undergirded as they are by a hidden armature, one that we almost feel rather than see. If in some paintings this armature emerges as a line echoing the predominant lay of the painting – vertical echoing vertical, horizontal re-stratifying horizontal – against a welter of countervailing strokes, in others it can be sensed in the strokes themselves, plied one against another in a free but even fashion.

Even in the square paintings of this series, where the gestures seem to tumble in random fashion, the apparently directionless motion starts to churn powerfully, agitating itself into a contained storm.

TRANS LUX

Peter Frank, Art Critic

In her Trans Lux series Dean Andrews focuses down onto, and into, a realm where picture transfers over into object.

In her Trans Lux series Dean Andrews focuses down onto, and into, a realm where picture transfers over into object.

The compact presence of these paintings and their granular, subtly lustrous surfaces divert attention away from what is composed on their faces and towards their physical presence. They are not supports for imagery, but for a material facture that at once tells the eye everything about itself and fools the eye into thinking there is more.

In this, Andrews explores a realm of perceptual elision proposed by fellow southern California artists in which the principal tenet of minimalism – what we see is simply what we see – is subverted by the vagaries of sight – what we see never stays the same.

Minimizing her compositional and coloristic strategems in the Trans Lux paintings, Andrews maximizes their active presence in our visual comprehension. They don’t quite disappear, but they do modulate in the presence of different light sources and different contexts of display.

These inert objects do not sit still for a second.

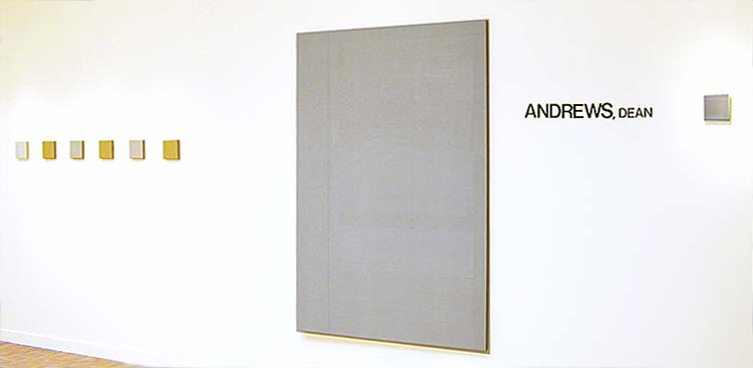

DEAN ANDREWS: LIGHT WATCH AT TAKADA GALLERY

Kenneth Baker, Art Critic, San Francisco Chronicle

Dean Andrews’ spare paintings at Takada register brushwork very faintly, surrendering most of their expressive energy to incident light. Mixing acrylic with glass microspheres, Andrews makes paintings that respond to every change of vantage point on the viewer’s part and every shift in light. In this respect, Andrews’ work resembles almost too closely that of Los Angeles painter Mary Corse. But Andrews deploys her medium at what seems like miniature proportions, while Corse’s paintings approach mural scale.

Dean Andrews’ spare paintings at Takada register brushwork very faintly, surrendering most of their expressive energy to incident light. Mixing acrylic with glass microspheres, Andrews makes paintings that respond to every change of vantage point on the viewer’s part and every shift in light. In this respect, Andrews’ work resembles almost too closely that of Los Angeles painter Mary Corse. But Andrews deploys her medium at what seems like miniature proportions, while Corse’s paintings approach mural scale.

Ask to view the show with the gallery lights off: By day, the paintings really come to life under the central skylight. An even sparser installation than we see at Takada would have strengthened the impression Andrews’ work makes.

A couple of large canvases ballast the show, but the smallest ones, each less than 6 inches square, find a perfect balance of unprepossessing scale and startling effect, cool objectivity and the power to dramatize unshareable optical sensations. Fragments of grid glow within Andrews’ black and pale green monochromatic squares, implying a delicate structure submerged in a brilliant fog.

When a local curator finally organizes the needed show surveying the influence of fog on art made in the Bay Area, Andrews will have a place.

SUBTLETY ALLOWS THE INTERIOR OUT, DRAWS VIEWER IN

Peter Steckel, Kirkland Courier

Viewers are most apt to be struck by the subtlety of Dean Andrews and her paintings. “Subtlety today seems to get overshadowed by, not only a barrage of imagery, but the speed at which it is shot at us and at which we are expected to assimilate it,” said Andrews during a recent interview. Where she works and lives is the antithesis of this barrage. “My productive time is spent in a quiet, contemplative, ‘interior’ place that doesn’t let much from the outside in,” she said. It’s a place where she can work in complete silence. “That is much of what is reflected in my paintings.”

Viewers are most apt to be struck by the subtlety of Dean Andrews and her paintings. “Subtlety today seems to get overshadowed by, not only a barrage of imagery, but the speed at which it is shot at us and at which we are expected to assimilate it,” said Andrews during a recent interview. Where she works and lives is the antithesis of this barrage. “My productive time is spent in a quiet, contemplative, ‘interior’ place that doesn’t let much from the outside in,” she said. It’s a place where she can work in complete silence. “That is much of what is reflected in my paintings.”

Perhaps because her work is subtle and doesn’t clamor for instantaneous and complete attention, Andrews recognizes that it demands something that all viewers may not be able to bring to it. “First of all, it requires slowing down enough to really see it,” she said. Andrews points to one of her great influences, Robert Irwin, who said, “Seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees.” It’s necessary to work in order to enter that, “wordless space where you are appreciating something purely for its beauty, for what it is offering you visually and aesthetically.”

Andrews equates it with the experience of, “Really taking the time to let a stunning sunset overwhelm you.”

There are signs of subtlety in art and sensibility (and even in marketing) all around us,. Andrews would have us look to the monochromatic advertising exhorting us to “Fall into the GAP” or to proposals coming in for the World Trade Towers Memorial, “One of which is simply two columns of blue light projected up into the sky as sort of ghost images of the towers.” For those who doubt the impact of art that does not immediately clout the viewer over the head with image and color, Andrews points to Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. “There is a long tradition of minimalism crossing all areas of creative expression, in architecture (Philip Johnson), music (Philip Glass), sculpture (Isamu Noguchi) and painting (Agnes Martin),” she added.

Coming from a large family, Andrews chuckles over the possibility that the minimalism in her art might represent that, “I’m still searching for a peaceful spot amidst the chaos!” But that would be too simplistic, especially for those who find a calm port in the storm when viewing her paintings. “I think appreciators and collectors of my work are those who are most easily transported to that place of quiet,” she said.

Artists such as Kenneth Noland, Agnes Martin and Frank Stella have influenced Andrews. “There is always a danger in people thinking your work is derivative but I think it’s pointless for an artist to give that consideration,” she said. Andrews sees it more as an exchange. “We all are influenced whether or not we choose to acknowledge it,” because, “there has been a dialogue among artists as long as there have been artists.”

This give-and-take colloquy between artists, writers, painters and musicians is occasionally, jokingly, referred to as “stealing.” It’s part of what makes for “movements,” “styles” or a musician’s “act.” And even creative artists who work outside the accepted artistic community, decrying its corruption or decline, are influenced by those around them.

Whatever their reference point, Andrews feels that artists have an obligation to make their art. Simply put, “Those who are gifted with the ability to express themselves ought to find a way to do it,” she said. And the public has a responsibility too. “If (an artist’s) interests are social or political and they have a means of expressing it, I think the rest of us have an obligation to actively listen,” to the, “chroniclers of our time.”

The interaction between artists and patrons is very intriguing. “They connect on a deeper level than the general observer,” said Andrews. “Art patrons often are as passionate about the work as the artist and feel a personal connection with not only the work but the artist as well.” All art, be it on the stage, a canvas, a book in your hands or shaping clay and stone involves a deep form of communication between people, with the art serving as the catalyst in the relationship. “Patrons make the difference in the amount of exposure an artist’s work receives which then directly influences the artist’s success,” said Andrews. “Having a champion on your side who appreciates and supports you unconditionally, as many patrons do, is a tremendous asset for an artist.”

YOU ARE HERE

Joseph Woodard, Art Critic, Los Angeles Times

Some art spaces are inspiring enough to affect the evolution of art they eventually host. Count the large, luminous gallery at the Brand Library in Glendale as one of them. And count this exhibition from painter Dean Andrews as one of those acutely site-specific artistic events.

Some art spaces are inspiring enough to affect the evolution of art they eventually host. Count the large, luminous gallery at the Brand Library in Glendale as one of them. And count this exhibition from painter Dean Andrews as one of those acutely site-specific artistic events.

Andrews developed her series of paintings, subtly layered and graduated works that suggest skyscapes, with the knowledge of the impending exhibition. A symbiotic relationship between art and walls is part of the ultimate, meditative charm.

She calls the show “You Are Here,” and her 15 uniformly scaled, 68-inch-square paintings go under the title “Presence,” a clear indication of her intent to celebrate this particular space.

As much an installation piece as a showing of individual works, the artist’s serial canvases make for a dramatic sight, in ways that seem both minimalist and monumental, with an effect both bracing and soothing.

The canvases, hung at precise intervals around the gallery, are stapled to the wall. They are denied frames, which tend to set up hierarchical separations between art and art space.

Although leaning toward soft shades of blue, green, gray and rose, Andrews’ art is deceptively calm and limited of palette. In face, delicate layers of color and flowing brushwork give the paintings personality, while adhering to a fairly strict, post-minimalist aesthetic. Yet Andrews’ brand of painting has a warm, objective lyricism instead of the cold, calculating snap of some minimalism.

If the end result of the exhibition is a kind of transcendental appreciation of the effects of light and color in a given, generous space, it is also a celebration of the purely physical aspect of a gallery – this gallery.

These paintings are illusory in that they evoke neatly framed expanses of sky or sea or pure painterly expression and exploration, but in the end, remain as paintings.

There’s nothing virtual about it. There lies part of the subtle power.

THE WILL TO PAINT: RECENT WORKS BY DEAN ANDREWS

Leslie Ava Shaw, Curator/Art Historian, New York, NY

Wassily Kandinsky believed that painting could represent the universal, that it could express the intense feelings of the artist and that it could exist without referring to the objective world. This gave license to those who followed especially Jackson Pollock whose search for an inner truth did not die with him. In this period of post-modernism that includes multiculturalism, gender identification, and institutional critique, the idea of making paintings with the intention of expressing the metaphysical continues to assert itself in the work of contemporary artists.

Wassily Kandinsky believed that painting could represent the universal, that it could express the intense feelings of the artist and that it could exist without referring to the objective world. This gave license to those who followed especially Jackson Pollock whose search for an inner truth did not die with him. In this period of post-modernism that includes multiculturalism, gender identification, and institutional critique, the idea of making paintings with the intention of expressing the metaphysical continues to assert itself in the work of contemporary artists.

Dean Andrews is one such artist who carries this tradition into the 21st century as a contemporary artist whose practice includes the use of unusual materials and innovative techniques.

Andrews has been making non-objective paintings, that is paintings without discernible images, for the past 20 years. Her most recent works contain bands with veils of color. The paintings are large in scale, sometimes as high as 138 inches and as wide as 104 inches. One such work is Decisive Eye, which is actually made up of three horizontal panels that join to make a vertical painting. Her tongue in cheek title obviously refers to an artist’s ability to make careful choices. In this work, the viewer will experience the full range of the artist’s practice. Blues, ocres, violets blending from thin to opaque, from matte to pearlescent, form streams of colored light as if an opal exploded and filled the wall with luminosity. Beyond the use of reflective, interference and other diverse pigments, her use of industrial glass microspheres is testament to the artist’s savvy in discovering how non-art material may be utilized to augment a desired effect.

The shape of the canvas as well as the scale play significant roles. The paintings’ largeness brings to mind Mark Rothko’s remark that when viewing a small painting, you remain outside the painting, whereas when the scale is enlarged and spreads above and beyond the viewer, the experience is one of envelopment so that you enter the painting. However, Andrews’ paintings are sometimes narrow verticals or horizontals such as Brad’s Pit 1 which is a narrow vertical 84 inches in height and 6-1/2 inches in width.

Pollock once said I feel like I’m in the painting. Andrews isn’t necessarily in the painting, but she appears to be of it because the tallness of the verticals may be a conscious or unconscious reference to her own sleek physique. Moreover, by virtue of its width, the painting becomes an object and its optical effect changes depending on the size of the wall on which it is placed. In this context, the work has a relationship to the wall where the wall becomes the background of the painting as in the work of Ellsworth Kelly whose paintings force the viewer to focus on the depth of color. In Andrews’ works of this type, color is also key. For example, in Brad’s Pit #3 the narrow vertical panel is saturated with fiery red and orange hues as if the impact needs to be contained lest these colored bands explode.

Andrews once again plays with established vocabularies albeit to her own liking. For example, the bands in Monumental Mystique are reminders of Barnett Newman’s zip paintings, only her “zips” are drenched with fresh, brushy combinations of color.

Randomness and order, both essential elements of nature, are combined in these recent works. For example, Mind Over Matter is a narrow panel containing stacked modules of transparent layers of color. These measured wide bands contain streams, waves and clouds of color that are organically rendered. These stacked sequences represent order. The cloud-like gestures of pink and gray separated from sections of puffs of cerulean blue and orange are evocative of nature’s indeterminate quality.

Suggestive of a sun-filled morning or an evening following a glorious sunset, nature is frequently called to mind, though subtly. In order to glean meaning from these canvases, one must be willing to contemplate the sheer beauty of their surfaces. One may experience these paintings as reminiscent of bathing in the sun’s nurturing light or embracing the night sky’s awesome constellations of sparkling lights against the vast darkness. But these paintings are not the sky nor do they represent it. In this respect, Andrews pays homage to Agnes Martin whose paintings of the last 30 years are minimalist abstractions that were created to take pleasure in the mere beauty of color and lines of graphite that are hand-drawn, yet contemplating them is similar to scanning the sky or looking into the ocean.

There are two camps of abstract art, one is abstraction as representing a realm that is larger than life, the other is the focus on the formal aspects of color, line, shape, and texture. Before abstract painting came into its own in the early 20th century, the Impressionist artists brought painting into the field of process. Their use of pigment directly from the tube, the mixing of colors on the canvas, and the application of patches of paint combined to make paintings that were a more immediate and spontaneous response to nature. However, if an artist is not painting from nature, that is from observed reality, the question remains, what is her intention?

In the late 20th century, Robert Ryman said, “There is never a question of what to paint, but only how to paint.” The final object is what the viewer witnesses, but the making is the experience of the artist’s alone. What motivates an artist to spend hours preparing and making the art only perhaps to begin again the next day because the final result is not what one had anticipated? It is the act of painting itself that motivates the maker. It is the joy of process that has come after years of practice, of experimenting with pigments and materials, with scale, shape and so on. It is a result of years of struggle. The beauty of creating abstract painting of this type, painterly, gestural and minimal yet contained within the parameters of a wide stretch of canvas on the floor is existential. It is the hand-wrought, the discernible movement of the artist’s hand on the canvas.

Andrews uses rough rags, thick house paint brushes and even her hands. She thins the paint or grabs it straight from the palette working up layers of color, playing opaque against transparent, matte against gloss, like-values against disparate hues. Areas of violently conflicting colors co-exist with passages of peaceful resolve. Her process also includes cutting the canvas in strips, then rearranging them. Engaged by the beauty created as the pieces are juxtaposed, slipped one against the other, the co-mingling of the bands is done viscerally and intuitively.

This technique is one the artist has developed on her own; it is a practice of self-discovery and experiment. It is a game that she enjoys playing as so many artists before her have, Picasso in particular and Pollock too where in Hans Namuth’s film he dances on the canvas, splattering paint on this spot and that is if possessed by none other than the momentum of his actions.

Finally, the success of Andrews’ paintings is the fact that they appear effortless. Her seductive surfaces that hold passages of warm glides coalescing with cool sweeps or endless columns that appear to trap burning embers of uncontrollable matter assert the desire to play, the need to organize, and the will to paint.

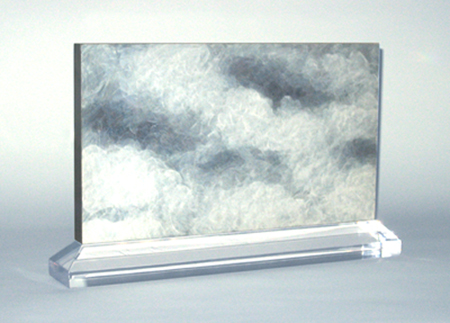

STRATA

Peter Frank, Art Critic

In her Strata series Dean Andrews would seem to be looking heavenward, or even borne aloft. Her renditions of clouds, as rich, aqueous, and natural-seeming as those found in Constable or Tiepolo, celebrate one of the world’s most evocative phenomena.

In her Strata series Dean Andrews would seem to be looking heavenward, or even borne aloft. Her renditions of clouds, as rich, aqueous, and natural-seeming as those found in Constable or Tiepolo, celebrate one of the world’s most evocative phenomena.

But, like any good cloud painter, Andrews is not just emulating the lofty fulminations of weather and atmosphere, she is capturing, reconsidering, and reinventing a visual space that has captivated humankind’s senses since our species began to reason.

Clouds, fugitive things, are among the most painterly phenomena in nature. They are nothing but brushstrokes. Especially when depicted on the scale Andrews has chosen for them here, they can disappear into abstraction, as tenuous in their presence as Turner’s fires or Monet’s water lilies.

This is what fascinates Andrews, a painter who favors the abstract but favors it for its ability to distill the essence of the world as we feel and see it.

Andrews does not invent her paintings so much as derive them from what she and we already know with our eyes and hands. In making that derivation, however, she paints in order to make us question what we thus know, and her clouds – miniature excerpts of vast skies, palpable but pocket-size cloud-things much more substantive but much less “real” than photographs of the same subjects – upend everything we know about the physical actuality of clouds at the same time they reify how we see them. Andrews’ clouds aren’t there, but they have been.

DEAN ANDREWS’ STRATA AT FIG GALLERY

Jan Butterfield, Art Critic and Author of The Art of Light and Space

“Sunrays strike through veils of misty dews…

“Sunrays strike through veils of misty dews…

How luminous the land that haze enshrouds

Struck by the blaze that falls through gathering clouds!”

Charles Baudelaire, Gathering Clouds

Dean Andrews’ new translucent skyworks on plexiglass, recently shown at FIG Gallery in Santa Monica are diminutive, ranging in size from 4 inches by 4 inches to 8 inches by 14 inches. These are a radical contrast to her previous site-specific work, “Atmospheres,” which incorporated canvases as large as 86 inches by 204 inches filling an entire room.

These exquisite works are not representational. They are not so much depictions of clouds or of summer or winter skies; they are, rather, images of infinity – tinted with color – glimpsed briefly, as out a window.

Of all the images at an artist’s disposal, none ride the tightrope between realism and abstraction as does the sky in its infinite intricateness. Few paint it well. One of those artists is Dean Andrews.

One of the more exciting and rewarding things in this complex art world is to witness the development which occurs when the sparks which jump from one artist to another spawn a whole new generation of legitimate inheritors. The newest works of Dean Andrews – the cloud and sky works – do just that.

Fleshing out a tradition begun in the 1960’s by Joe Goode, Andrews’ cloud works are clearly influenced by “Light and Space.” More specifically, they also fit even more comfortably into the sub-category, dubbed, somewhat prosaically “California Glass and Plastic,” which came to the fore in Southern California in the late sixties.

The effect of California as a place has had a great influence on works of “Light and Space.” The sunny skies, sparkling water and soft sand are as much a part of the feeling of this place as the subways, skyscrapers and gridded streets are of Manhattan.

To live in California is to be continually conscious of the curiously softened color and of space. The quality of light is striking. Even the smog has its positive attributes: the striations of soft yellows and lavender in the inversion layers are almost more spectacular than any clear-sky effects ever seen there. When the noise and traffic become unbearable, there is always the desert – whose vast stretches calm, reassure and restore.

The difference between East Coast artists and West Coast artists became patently clear at this point in time. East Coast artists wanted the object and the material to be separable, whereas those on the West Coast sought to make the statement separate from an object; they wanted to suggest the ripple of the sunlight, the flicker of light through the trees, a smooth spill of moonlight. As the critic Melinda Wortz put it: “The illusions found in these Southern California works – of solid forms, dissolving through reflected or projected light…resulted from an interaction between the ambient light and the objects themselves. In other words, these works incorporate the light and space of the place they are in, rather than painting the illusion of colored light on canvas.”

The transparency and seeming immateriality of glass and plastic made them ideal for concerns with light, space and color. The works created in that tradition, though still object-oriented, became very experiential, particularly as successive refinements started to take place.

With the widespread involvement with “Glass and Plastic” the boundaries between painting and sculpture began to dissolve. Dean Andrews’ works are superb examples of works which have learned their lessons from “Light and Space” and “California Glass and Plastic,” and have gone on to make a very real contribution to the establishment of an art form that is neither painting or sculpture per se but a highly successful amalgamation of them both.